How to choose between two-mass and brute force vibratory screen designs

The type of screening system impacts energy use, component wear and maintenance, and uptime on site

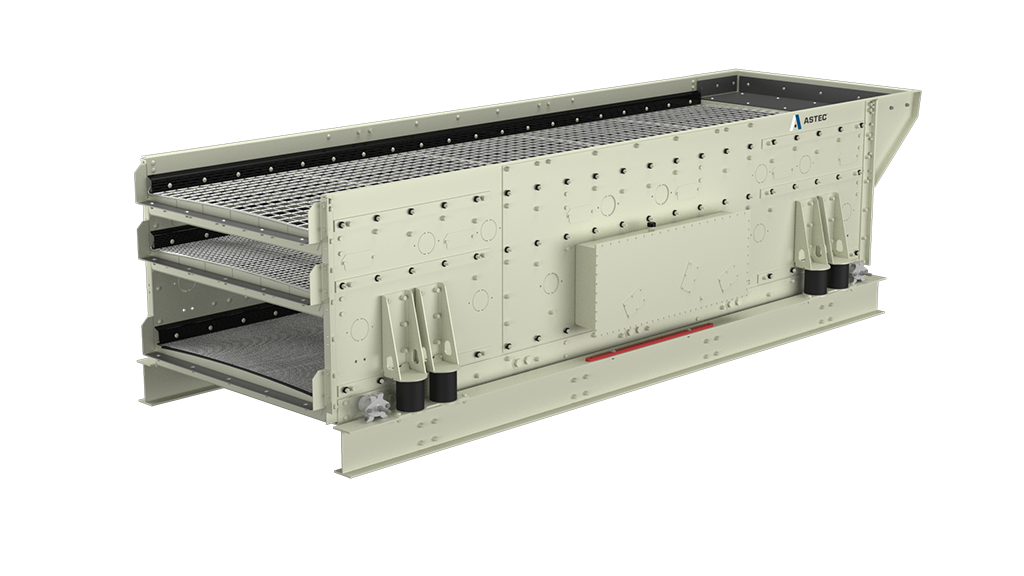

Vibratory screens are a critical component in applications like aggregates, mining, roadbuilding, and construction, where screen performance directly impacts productivity and uptime.

But not all screens are created equal. Beneath the motion lies an important design distinction: whether the screen is powered by a two-mass system or brute force. While both approaches aim to separate material effectively, the way they generate and manage vibration can significantly impact energy use, component wear and maintenance, and uptime on high-tonnage construction and aggregates sites.

"When you add weight to a brute force system, performance goes down," explains Bob Huffer, director of recycling at General Kinematics (GK). "But with a two-mass system, it actually improves."

Huffer has spent decades advising construction professionals on screening technology, especially for challenging material streams like concrete, asphalt, and high-volume demolition debris.

While both systems serve the same purpose, the design differences are substantial, and those differences show up in everything from energy efficiency and scalability to how they respond under load.

How to understand the two systems

Brute force systems operate on a simple principle: a motor is mounted to a single mass, essentially a steel box, supported by isolation springs. When powered on, the eccentric motor shakes the entire unit.

"The bigger that box gets, the more energy, the more horse-power you need to drive that," says Huffer. Additional or larger motors are required to maintain performance.

Two-mass systems take a more engineered approach. Rather than forcing vibration through a single body, they use two masses connected by springs. One mass contains the motor where the vibration is created. That vibratory energy is then amplified through springs into the second mass, where the material is handled. This configuration allows the two-mass system to operate near its natural frequency, where a minimal amount of energy is needed to do the same or more work than a brute force machine. The result is a more efficient transfer of motion and significantly lower energy demand.

"In general, you're looking at 40 to 60 percent less horsepower [for two-mass] compared to brute force," says Huffer.

Efficiency and performance under load

Where the two systems really diverge is in how they respond to changes in material load. In brute force systems, increasing the weight of the load dampens the stroke, essentially reducing the amplitude of the screen's motion. This results in reduced material movement, slower processing, and lower overall capacity.

Two-mass systems behave differently. As more weight is added, the stroke increases due to the natural frequency effect. This effect makes them better suited for high-volume or heavy-load applications.

How to choose the right system

Two-mass systems are a good choice for large-scale, fixed recycling facilities. According to Huffer, GK's systems can weigh upwards of 85,000 pounds and are designed to handle up to 1,400 tons per day of construction and demolition material. These installations often include custom finger screens and integrated components tailored to the plant's material flow and space constraints.

Brute force screens are more common in compact or mobile applications, such as aggregate screening trailers or under-crusher feeders. Their simplicity makes them easy to maintain in tight quarters or when weight and space are limiting factors.

"There are still cases where brute force makes sense," says Huffer. "It's a simpler design with fewer components, and sometimes that's what the site demands."

Managing vibration and structural impact

Another advantage of the two-mass design is its ability to manage dynamic forces. Because the two masses move in opposite directions, they cancel out a significant portion of the vibration that would otherwise be transmitted to the foundation.

According to Huffer, this cancellation effect can reduce dynamic forces by up to 80 percent. This is a crucial benefit when installing heavy equipment on lighter foundations or in older facilities. It also minimizes the risk of vibration damage to nearby structures or equipment.

Maintenance, scalability, and longevity

Brute force screens offer a simpler mechanical design, with fewer components and no counterbalancing mass. With fewer moving parts and a straightforward drive mechanism, brute force systems are often easier to install, troubleshoot, and maintain in compact or remote set-ups.

However, that doesn't necessarily equate to longer life or lower maintenance over time. Brute force systems hit design limitations when scaled up, making them less suitable for larger or high-tonnage operations.

Two-mass systems, by contrast, are built for scalability. Their design allows machines to be constructed wider and longer without losing stroke or efficiency. This means operators can process more material in a single unit, increasing throughput without expanding their equipment footprint. It also opens the door to custom configurations tailored to high-tonnage applications where brute force designs would struggle to maintain consistent performance.

When it comes to wear and maintenance, both systems are comparable, provided they're processing similar volumes. "Wear is probably equivalent if you're comparing the same tonnage," says Huffer.

Screen types and customization

General Kinematics offers three primary screen designs under the finger screen category: Traditional, Free-Flow, and Velocity (formerly known as FINGER-SCREEN 2.0). Each is built on a two-mass platform but optimized for different materials and system configurations.

Traditional finger screens use a counterbalance beneath the screen to stabilize motion and are ideal for high-volume, rugged applications.

Free-Flow screens eliminate the lower conveying pan, allowing all material to drop through onto a belt. This open-deck design minimizes material buildup and simplifies maintenance, making it especially effective when processing sticky or wet fines.

Velocity screens use multiple screen bodies running out-of-phase to maximize stroke and movement, making them well-suited for light or bulky materials like cardboard.

Choosing between screen types depends on feedstock, separation goals, and job site layout. "It's about the type of material, the size you're trying to separate, and how much volume you're dealing with," says Huffer.

Handling difficult feedstocks

Both systems can be used with wet or sticky materials, but the longer stroke and higher energy of two-mass systems make them more effective in these scenarios. The increased vibratory energy helps prevent material from clumping or clogging.

When feedstock is inconsistent or surging, as is often the case in C&D applications, the responsive stroke of two-mass systems enables them to adapt in real-time, spreading material more evenly and maintaining throughput.

When to upgrade

For facilities that currently use brute force systems, upgrading to two-mass can offer a path to greater capacity without increasing footprint. In some cases, a plant can handle significantly more throughput simply by swapping in a two-mass system tuned to the existing space.

Huffer notes that upgrading to a two-mass system is often a natural step for facilities looking to modernize or expand. For operations aiming to boost capacity by 20 to 40 percent, switching to a different screen design can be the most effective solution.

What's next for General Kinematics?

As customer demands evolve, GK is continuing to scale its technology. In 2023, the company built its largest finger screen to date: seven feet wide and 50 feet long, and weighing in at 130,000 pounds. It was developed to meet growing demand for high-throughput screening in a single unit.

Increasingly, the company is designing integrated systems that combine screens, feeders, and downstream equipment into cohesive, high-throughput workflows for construction material handling. According to Huffer, this shift reflects a broader trend across the industry: reducing manual labour while maximizing throughput and efficiency.

Designing effective screening systems isn't just about choosing the right machine. It's about engineering for the feed material, footprint, and long-term scalability. For construction and aggregate producers, two-mass screens offer clear advantages in energy efficiency, foundation protection, and high-volume capacity. But in mobile set-ups or tight job site conditions, the straightforward design of brute force screens still delivers value. For contractors and operators looking to boost throughput or adapt to changing material demands, the right screening system can unlock new productivity without requiring major infrastructure changes.

This article originally appeared in the 2025 November/December issue of Heavy Equipment Guide.

Company info

5050 Rickert Rd.

Crystal Lake, IL

US, 60014

Website:

generalkinematics.com/recycling-equipment